Colombian drug lord Pablo Escobar killed 30 years ago this month

Questions remain about who exactly fired the fatal shot

Warning: This blog contains graphic images that some readers may find disturbing.

Thirty years ago this month, the bloody reign of the world’s most wanted narco kingpin came to a violent end. As Colombian forces closed in on drug lord Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria, the old cliché rang true: “Live by the gun, die by the gun.” On December 2, 1993, Escobar was shot and killed atop a terracotta roof in a Medellín suburb.

The epic tale of Pablo Escobar involves an eclectic cast of characters whose stories garnered fame for some and infamy for others. From books to movies to TV series, supporting players in the larger drama have included Griselda Blanco, George Jung, Barry Seal, Jack Carlton Reed, Carlos Lehder, Manuel Noriega and the Drug Enforcement Administration’s Steve Murphy and Javier Peña.

Escobar amassed so many enemies that neither his vast wealth nor fear tactics could provide him with any solace or protection, especially in the waning years. Few remained loyal and those that did were picked off by the law, military or vigilante posse. With his days numbered, the ever-defiant Escobar tried to evade the multipronged front hunting him down, literally to his final moments.

However, the chapter did not fully close there, as is often the case with legendary figures and dramatic downfalls. Conspiracies and conjectures circulated regarding the circumstances of his death. Among them are legitimate questions that remain intriguing.

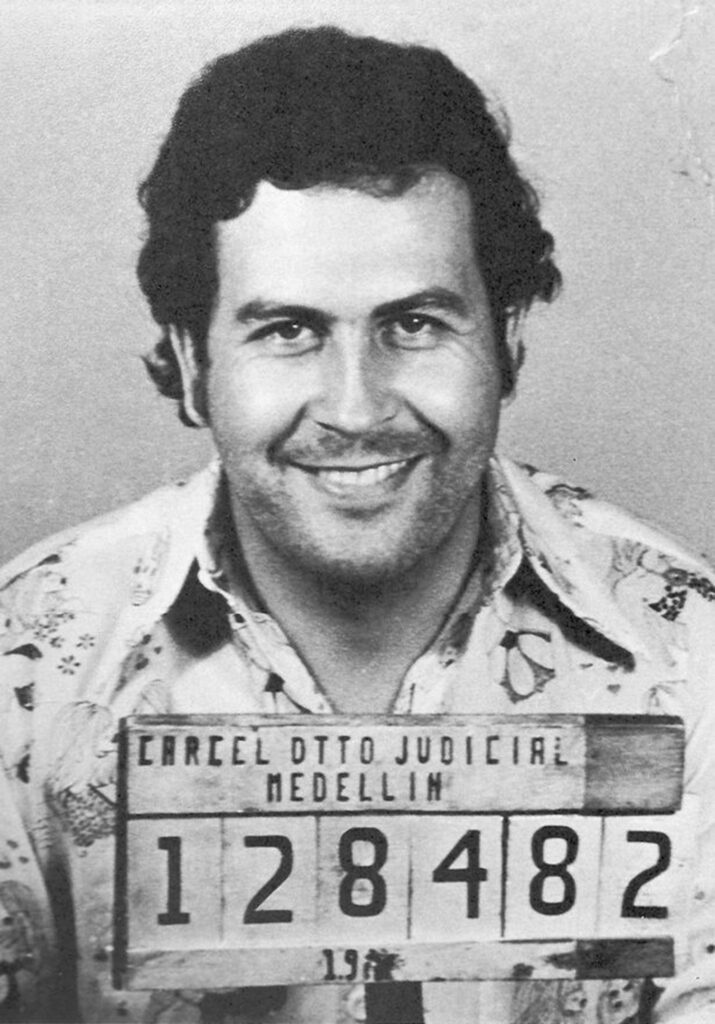

The high life

Most of what we know regarding Escobar’s early forays into crime comes from hearsay, folklore and a handful of accounts shared by surviving friends and family. Almost all versions share a few common denominators: Escobar started with small-time theft, smuggling and marijuana dealing before graduating to international drug trafficking. Other tales speak of kidnappings and murder. His first major arrest occurred in 1974, an auto theft charge for which he served several months. He graduated to the big leagues with remarkable speed, entering a business where an old narcotic substance had gained a renewed, glamorous popularity in the United States and Europe.

Capitalizing on the demand for cocaine made many independent traffickers wealthy. Some combined forces into “cartels,” but that is probably a misnomer. With respect to its strict definition as a coalition of colluding price-fixers, oversight committees and academics have noted that many people call the group by a more fitting name: the “Medellín Mafia.”

Still in his 20s, Escobar was already enjoying the spoils of money, power and an increasingly dangerous reputation. On June 9, 1976, a drug raid conducted by the Colombian intelligence agency (also known as DAS) netted about 40 pounds of cocaine base (crack) hidden in a car tire. The bust resulted in the arrest of six co-conspirators, including Pablo Escobar and his cousin/right-hand man Gustavo Gaviria. Escobar manipulated the system and swiftly got the whole crew out of the mess, but another judge had him rearrested. That also ended in Escobar’s favor, and he would later exact revenge on the judge and two police officers. That drug charge, however, would come back to haunt him.

Primed for violence

Buzzwords like “cartel” and “narcoterrorism” entered the world’s collective lexicon at the height of cocaine’s violent era in the 1980s. A series of crucial turning points gave rise to this new reality.

First, the once-independent barons pooled their respective talents and supply chain controls into a loose alliance. Soon after, they faced an imminent threat from paramilitary groups who used kidnappings to extort the wealthy kingpins. In solidarity, narco bosses from various factions and regions delivered a vicious response to the militias: “Death to kidnappers.”

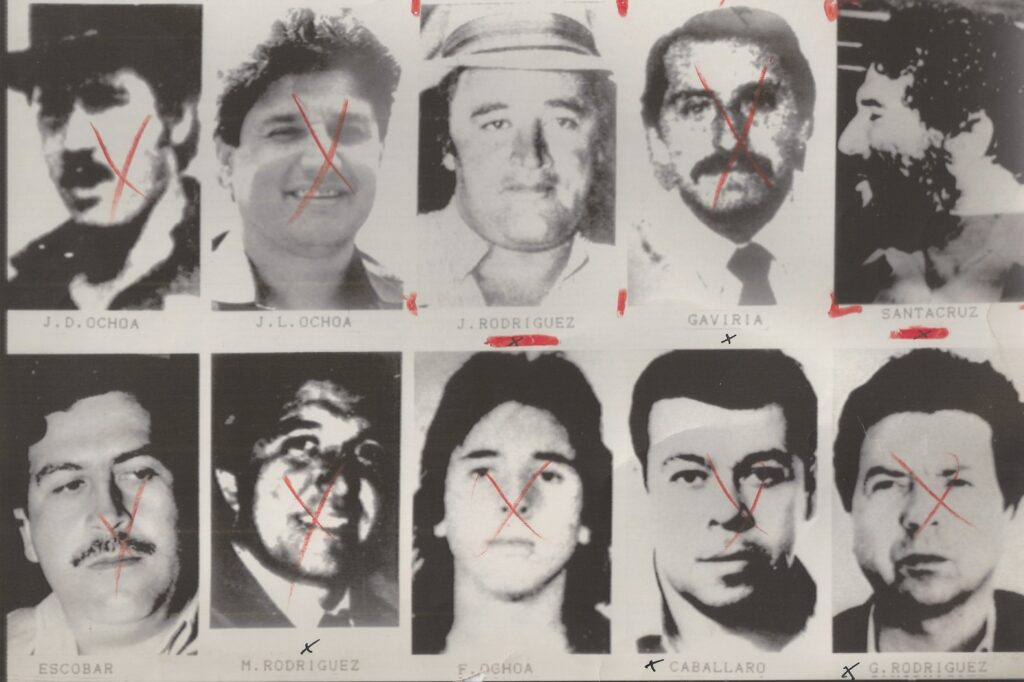

Another issue facing the traffickers, the ultimate flashpoint, was a 1979 extradition treaty between Colombia and the United States. Although it was initially seldom used, by 1981 the threat of its use grew as the U.S. began indicting people like Escobar and fellow cartel members Carlos Lehder and Jorge Ochoa.

Always ambitious for greater power, Escobar campaigned for a seat in Colombia’s parliament (and the diplomatic immunity that came with it). In November 1982, he was elected as a substitute for Jairo Ortega. To his surprise, perhaps, some politicians publicly questioned his business dealings, insinuating narco-affiliation. This, at first, led to a war of attrition. Escobar and his allies cast accusations back at their accusers, but by August 1983, the ghost of the gangster’s past returned.

Compounding the accusations of his rivals in congress, ABC News premiered a special, “Cocaine Cartel,” which featured an interview with Escobar. In the segment, Escobar, like the others who agreed to be interviewed, denied narco involvement, postulating rather matter-of-factly: “If there had not been an influx of hot money or dollars into the country, then the country would be suffering a grave economic crisis similar to that of other countries of Latin America.”

Detractors were quick to use the “hot money” statement against him. Just days later, the Colombian newspaper El Espectador resurrected its 1976 article covering Escobar’s drug bust. First stripped of his immunity, Escobar eventually bowed to the pressure and resigned in January 1984. But he would get his revenge.

The Medellín faction pivoted to a public relations campaign, creating “Los Extraditables.” The shadowy group distributed literature and sent out letters condemning Colombia’s extradition treaty, attempting to win over the masses. “But the group called ‘The Extraditables’ was a nickname that Pablo gave himself,” said Ochoa in a 2000 interview with Frontline, “so that he could direct all his violence and his terrorist actions towards the extradition.”

Escobar unleashed a retribution that shook Colombia to its core, including murders, bombings and a literal declaration of war against his own country. From 1984 to 1991, Escobar was directly blamed for the assassinations of political adversaries, police officers and the editor of El Espectador. Among the most reprehensible acts linked to him were the two-day siege of the Palace of Justice (98 dead and his extradition documents conveniently destroyed), the bombing of Avianca flight 203 (107 dead), and the DAS building bombing (60 dead and more than 600 wounded).

Conditional surrender

On September 5, 1990, Colombia hoped to bring the bloodshed under control by instituting a program of partial amnesty and promising no extradition. Traffickers began to trickle in, including two of the Ochoa brothers, by the following January. Escobar, however, held out until June 1991, when the extradition ban formally entered the constitution. Escobar publicly stated that he agreed to surrender “because I could not remain indifferent before the longings for peace of the vast majority of the Colombian people.”

Accompanied by Catholic priest Rafael Garcia Herreros, Pablo Escobar turned himself in to Colombian authorities on June 19. He handed over his personal effects, including a Sig Sauer 9mm pistol. Per the agreement, authorities took him to a special prison facility southeast of Medellín. La Catedral, unofficially called “Hotel Escobar,” was designed and built to his specifications and included amenities such as a disco and a jacuzzi. This so-called incarceration seemed a mockery, so the United States continued to pressure Colombia.

For Escobar, everything remained business as usual. Rumors of lavish parties and general debauchery going on inside La Catedral circulated among the public. There were even allegations of murder on the premises. Colombia’s government had to do something.

In July 1992, Escobar got word of the government’s plan to move him to another facility. On July 22, Escobar and nine others fled into the surrounding woods as forces approached the prison. A day later, his lawyers delivered a list of conditions for their client to re-surrender. This time, Colombian authorities had no interest in negotiations.

End of days

Escobar remained on the run and ordered more attacks, while the price on his head grew larger. Colombia’s elite Search Bloc, formed specifically to hunt Escobar, had the support of the DEA, Delta Force and Navy Seals. Over the previous years, Escobar’s violence even made some of his own members turn against him. Los Pepes – an acronym meaning “the Persecuted by Pablo Escobar” – was a group made up of former allies, paramilitary and angered citizens (and purportedly funded by the Cali Cartel) who worked outside the law to flush the fugitive out. They killed anyone associated with Escobar.

On December 2, 1993, one day after his 44th birthday, Pablo Escobar and his chauffeur/bodyguard, Álvaro de Jesús Agudelo, also known as “El Limón,” were virtually hiding in plain sight. They might have thought the police would never expect them to lay low in Escobar’s own hometown area.

Search Bloc was closing in on Escobar, thanks to successfully triangulating an uncharacteristically long phone call. A member of the team spotted a man in the second-floor window of a row house. The long-haired, full-bearded man in the window looked different than the Pablo Escobar from their photos. But it had to be the guy they were looking for.

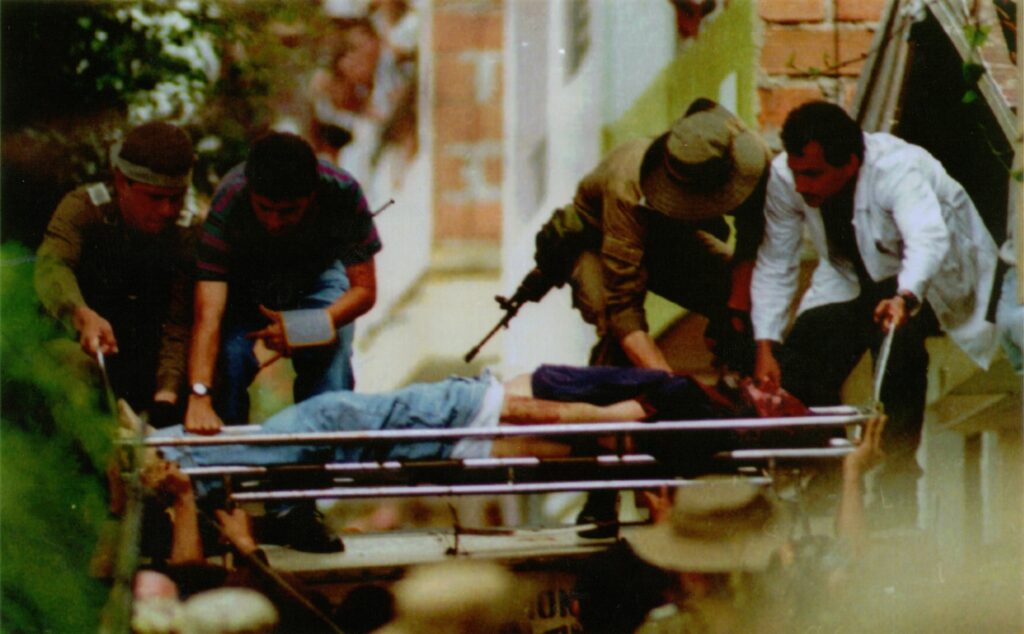

As Search Bloc surrounded and entered the house, Limón fled out a window. He dropped to the lower roof but was hit multiple times while running and plunged to the ground below. Escobar – armed with two pistols, including the Sig Sauer he had turned over in 1991 – attempted the same escape route via the roof but was struck three times in the left leg, upper right back and right ear. Both men lay dead.

Who fired the killing shot? Plenty of people wanted to take credit. Search Bloc’s Hugo Aguilar was the most notable to claim responsibility. Diego Murillo Bejerano of Los Pepes, also known as “Don Berna,” claimed his brother did it. Conspiracy theorists insist it was U.S. agents. It was a mystery right out of the gate because the takedown happened very quickly without many onlookers. Would-be witnesses were taking cover in their homes when the gunfire erupted. The first photos taken of the scene were snapped by DEA agent Steve Murphy, who didn’t arrive until after Escobar was dead. Then, the scene itself – and subsequent medical examination – was a chaotic mess of people shuffling through, a crime scene gone wild.

Exploration into the controversy has continued over the years. In 2006, Escobar’s body was exhumed to settle a paternity test but provided little to no updated forensic information.

More recently, a 2020 episode of the television series The Curious Life and Death of… examined the original autopsy. They conducted their own tests to determine the caliber of the fatal bullet and who may have fired the shot that felled the kingpin. They used ballistic gel dummies for their analysis, which concurred with previous findings: neither the bullet through Escobar’s leg nor the shot to the back, which lodged in the neck region, were fatal. The head shot was indeed the cause of death, but they ruled out previous claims that the round came from a rifle. Their tests echoed a theory that has circulated since Mark Bowden’s 2001 book Killing Pablo: a 9mm gun delivered the fatal bullet, possibly at close range.

The lack of gunshot residue, or “tattooing,” on the entry wound cannot be conclusively explained, except for the possibility that Escobar put the barrel directly to his own ear, or someone else did, as Bowden suggests. Bowden points out that Limón’s forehead also bore an unusually accurate gunshot wound. Whether self-inflicted or coup de grâce, it is possible that little or no gunshot residue would be found on the entrance wound. The show found that at that close range the residue would blast right through along with the round. Some of Escobar’s surviving family are convinced he took his own life.

The official autopsy, one of the sole sources of evidence, also had its peculiarities. Most coroner’s reports don’t come with a press release attached, as one of the show’s investigators pointed out. Also odd, they explained further, is that the press release apparently went above and beyond to specifically discount suicide.

With plenty of questions and not many concrete answers, a few additional developments over the years simultaneously shed some light and left us hanging. Regarding Los Pepes, they reportedly had contact or relations with Search Bloc and U.S. agencies. Yet some of their own commanders denied any involvement or presence that fateful day, contradicting Don Berna’s account. Years after Escobar’s death, Aguilar, whose claims have largely been discredited, found himself in hot water on corruption charges in the political realm. In an interview that surfaced in 2017 (from a defunct documentary film), he admitted to secretly exchanging his own gun for Escobar’s Sig Sauer at the crime scene.

Christian Cipollini is the author of Murder Inc.: Mysteries of the Mob’s Most Deadly Hit Squad and LUCKY, a gangster graphic novel.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org